Ever since I was a little girl, I have adored elephants. Such intelligent creatures and so human-like in their emotions and social values. I had seen them in the wild in Tanzania. I had experienced the amazing work that the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust does with orphaned elephants in Kenya. This only deepened that love and pull towards getting to know more about them and protect them from cruel elephant practices carried out in the name of tourism.

It took me a while to write about my experiences with elephant camps in Thailand and Sri Lanka. I get emotional every time I think about it. But I had to write about them. It will help to get the word out about how to approach elephant tourism, particularly in developing countries, and avoid cruel practices. It may help people understand the plight of these magnificent animals.

The day I met Soi

I had been travelling for a few months through Southeast Asia and ended up in a small town in the mountains of Thailand called Pai, just north of Chiang Mai. It’s a popular spot for digital nomads like me. Famous as a hippie town, its popularity was growing fast among travellers. I needed a place to drop my backpack, rest for a while and catch up with some work. I rented a bungalow surrounded by rice paddies and a moped to get around with, enjoying a slower pace of life for a while.

On one of my moped rides I found an elephant camp just outside town that had two elephants. Most importantly, it did not allow riding. Whatt started out as an afternoon having fun helping an elephant bathe in the river quickly developed into a deep, life-changing love and affection.

Soi (her name means necklace in Thai) was a female elephant, enjoying an early retirement from the logging industry. She spent her days splashing about in the river and munching on bamboo and bananas, humouring us humans who wanted to spend time with her. She took to me as quickly as I took to her, letting me stroke her trunk within seconds of meeting her.

After a few visits she would press her trunk against me looking for me to stroke the more sensitive underside. It’s one that elephants won’t often let humans touch. She also let me introduce her to everyone who stopped to feed her and say hello. It was an incredible feeling to know that she was slowly building a relationship with me. If I stayed long enough, perhaps I could have a fraction of the connection she had with her own handler (mahout), whom she clearly adored.

Looking for elephant volunteering opportunities

I couldn’t stay in Thailand forever. So I began to research opportunities to volunteer with rescued elephants and eventually discovered a US-based organisation that runs volunteering programmes in Sri Lanka. I applied for a two-week stay. They quickly accepted me and assigned me to an elephant camp in the town of Kegalle. It would mean spending my birthday among these beautiful pachyderms, so I was beyond excited; what better way to celebrate than by shovelling elephant poo and lugging around bamboo for their dinner?

Just before I was due to fly out to Sri Lanka, I began to investigate the camp itself a little more. I was horrified to find out that they make a lot of their money – allegedly to support their rescue programme and provide food and care for the elephants – by offering elephant rides to tourists. Furious, I wrote to the organisation’s headquarters. I demanded to withdraw from the programme and get a full refund on the basis that none of this information was available when I signed up and that they supported cruel elephant practices. They tried to argue, even making the point that the elephants are trained for riding, which only horrified me more. After a lot of wrangling and emailing, I finally succeeded in getting my money back.

After my initial protests, the organisation had offered me a spot at an alternative camp at Pinnawala. Close to Kegalle, it did not offer elephant rides. But my research showed that the conditions in which the animals are kept are not ideal either. I was determined to raise awareness of how the elephants were treated and looked after and of the cruel practices the handlers employed. So I decided to visit Pinnawala to see for myself how things were there.

What’s Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage really like?

I arrived around bath time, just as the elephants marched down the hill to the river. I quickly bought my ticket, keeping my reasons for being there to myself, and wandered off to watch the elephant procession.

There’s something about watching a herd of elephants amble along, knowing they’re on their way for some relaxation and a splash around. Even the oldest matriarch can act like a juvenile when in the water! For a moment it brought the smile back to my face. There were 28 elephants in total on their way to the river, ranging in age from the older matriarch to young babies.

That smile vanished pretty quickly when I witnessed the cruel elephant practices employed. It was soon obvious that the elephants feared the handlers. It was clear in their eyes and in their behaviour. I spent two hours observing them in the river. One of the younger keepers was a bit too liberal with the bullhook. I also watched him and another keeper throw sticks at the elephants when they weren’t doing what the keepers wanted and they couldn’t be bothered to round the elephants up. His voice was not authoritative and none of them seemed to have any relationship with any of the elephants.

The matriarch’s keeper used the bullhook a lot. Although the only chained elephant, she was chained for a while, nonetheless. Chaining may be necessary at times. Elephants are huge animals and are still wild. A rampaging elephant can cause a lot of damage and potentially kill people and livestock.

But chaining an elephant when it’s in the water robs it of the ability to comfortably rest its joints and cool off. And there’s more than one way to chain an elephant. When they are in their stockades or feeding stations they still need room to move around. One chain should be sufficient, if it’s even necessary. Two – one on the front and one on the back leg with no give, as I witnessed – is not the way to do it. An elephant literally cannot move, making it one of the more cruel practices used.

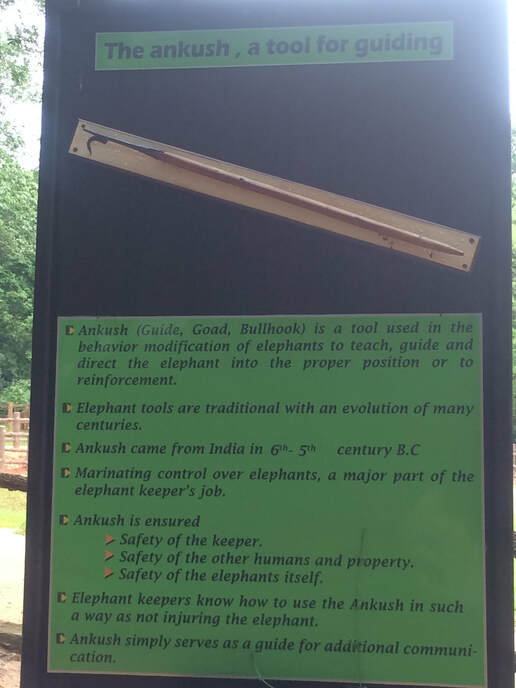

The bullhook

Let me dispel some myths about the bullhook. It is a long, spear-like instrument with a hook on the end, used to jab an elephant’s most sensitive spot, the toe. Ostensibly, it is used to protect humans and animals from elephants who are too boisterous or aggressive. There were a lot of posters about bullhooks around the site and they offered a one-sided view of the need for it.

You do not need to hurt an animal for it to listen to you. You need to build trust. I thought back to Soi and her mahout. Not once did I hear him say a harsh word to her. I never saw fear in her eyes. But all I saw was fear in the expressions of these poor Pinnawala elephants down by the river.

What was it like at the orphanage?

There, elephants were chained to their feeding stations. Two short chains, one on the front and one on the back leg. The representative who had been writing to me had been adamant that the babies are not chained. Absolutely not true – that is not what I saw.

I spent some time talking to one of the assistant keepers who spoke good English. It was clear he cared about the animals. He confirmed they’re all chained in the evening, babies included. He kept saying that it’s for their protection. But some better-built stockades should negate the need for that, irrespective of the amount of space the elephants have.

He also told me that the ratio of elephants to keepers is 1:1. But this isn’t what I saw by the river. I also asked him about the bullhook, and got the same story about protection and was told it’s part of a carrot-and-stick approach to keeping the still half-wild elephants in line. I mentioned what I’d seen at the river and the keepers’ behaviour. He told me that the previous year they had fired someone for being a little too fast and free with it.

He was much more affectionate with the animals. There was a young elephant that he was trying to treat as we talked, who’d had his tail bitten by another elephant and needed medication. The elephant was having none of it though. To him, being handled for medical treatment was the same as being controlled in any other way. It took two men to spray the syringe-full of medicine onto his injured tail.

What can change?

I left feeling dejected. I was glad that I had managed to avoid supporting such cruel elephant practices by not volunteering with the organisation. But I had hoped that what I had read about the treatment of the animals was untrue or an exaggeration. Sadly, it was not.

Ultimately, these orphaned and rescued elephants do need to go somewhere to be fed and looked after. What I thought was missing from the sanctuary was a more balanced education around the gentle nature of these giants. Their human-like traits and the importance of socialising to them. Why being comfortable in the water is so necessary for their well-being. There should be more information on the effects of using elephants for tourist rides: how they are trained for it and why it’s detrimental to the animal. Why using chains and bullhooks is likely to do more harm than good. There are sanctuaries that manage to have happy animals without any cruel practices, so it is not without precedent. Take a look at the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust for a more humane way of looking after elephants.

What can you do?

First and foremost, please, never ride an elephant. Know that if you choose to do so, the elephant has most likely been abused to tame it and break its spirit. Using bullhooks, beating, even starvation, humans will “break” an elephant with such cruel practices. They will make it accept a heavy basket on its back without objection, on one of the boniest parts of its spine. They will add to that the weight of western tourists – often overweight tourists. Then they will make the elephants walk on roads, where it hurts and burns the soles of their feet.

Imagine walking barefoot on hot tarmac, in the middle of a hot tropical afternoon. Now imagine adding the weight of an adult on your back, and you begin to get a sense of how it must feel.

Do your research before visiting any animal sanctuary. Make sure you’re not inadvertently supporting inhumane practices or involuntarily supporting the harming of animals. If you’re unsure, don’t do it. I have learnt my lesson the hard way. While I still have reservations about zoos, sanctuaries, safari parks and the like, if it is the only place where an animal can be looked after when it can’t do it alone in the wild, then as long as it is treated well, I am okay with it.

Post updated June 2025